Dental implants have revolutionized the way we restore missing teeth, providing patients with long-term, functional, and aesthetically pleasing solutions. Traditional or conventional implants, which anchor into the alveolar bone of the upper or lower jaw, are the most commonly used type of implant. However, in cases of significant bone resorption or severe maxillary atrophy, conventional implants may not be viable. In these situations, zygomatic implants offer an alternative by anchoring into the zygomatic bone (cheekbone), bypassing the need for bone grafting or sinus lifts.

Despite both being used to replace missing teeth, zygomatic implants and conventional implants differ significantly in their design, placement technique, indications, and potential outcomes. Understanding these differences is critical for choosing the best approach for a patient. This article explores the five key differences between zygomatic and conventional implants to help dental professionals make informed decisions in complex cases.

1. Anatomical Considerations: Implant Placement

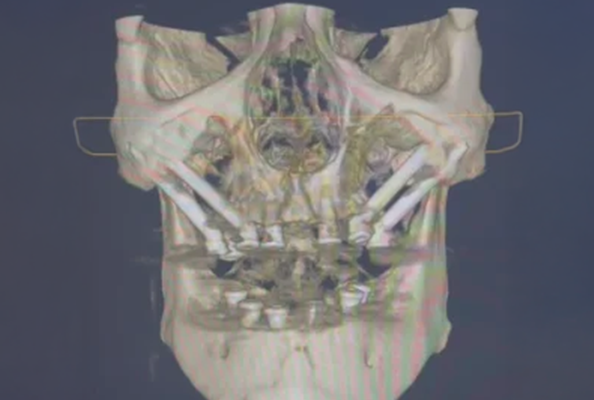

The most fundamental difference between zygomatic and conventional implants lies in their placement location. Conventional implants are placed directly into the alveolar bone, which is the bone that supports the teeth in both the upper and lower jaws. In contrast, zygomatic implants are placed into the zygomatic bone, which is the bone of the cheek, situated much higher and further back in the face.

A. Conventional Implants:

Conventional implants typically anchor into the alveolar ridge, which is the ridge of bone that holds the tooth sockets. This ridge is located in the upper and lower jaw and has adequate bone in most patients, especially those who are edentulous or have a healthy jawbone. The size and shape of the alveolar ridge may vary depending on the patient’s oral health, but it is generally the preferred site for implant placement due to its relatively accessible location and predictable outcomes.

B. Zygomatic Implants:

Zygomatic implants, however, are placed in the zygomatic bone, located in the lateral aspect of the maxilla, near the cheekbone. The zygomatic bone is significantly denser than the maxillary alveolar bone, providing an excellent anchorage for implants in patients who have suffered severe resorption of the maxillary ridge. Zygomatic implants are much longer (typically 30–52 mm) and are placed at an angle of approximately 45–60 degrees, angling towards the back of the maxilla.

Because zygomatic implants use a more posterior, lateral bone structure for anchorage, they are ideal for patients with severe atrophy or loss of the maxillary ridge where conventional implants cannot be placed.

2. Surgical Technique and Complexity

The placement technique for zygomatic implants is more advanced and technically demanding compared to conventional implants. While both types of implants require precision, the complexity of zygomatic implant surgery arises from the need to navigate a different anatomical region and the longer implant design.

A. Conventional Implants:

Placing conventional implants generally involves the following steps:

- Incision in the gum tissue to expose the underlying bone.

- Drilling into the alveolar ridge to create a site for the implant.

- Placement of the implant into the bone.

- Healing period of approximately 3–6 months for osseointegration before attaching the final restoration.

The procedure is typically straightforward and can be completed with local anesthesia in most cases. The surgical risks are generally low, with a shorter recovery time compared to zygomatic implants.

B. Zygomatic Implants:

The surgical process for zygomatic implants is more intricate and involves:

- Incision and flap elevation to access the zygomatic bone, often in the posterior maxilla near the sinus cavity.

- Specialized drilling to create a tunnel into the zygomatic bone, angling the implant at 45–60 degrees.

- Implant placement into the zygomatic bone, often using longer implants to ensure stability.

- Immediate loading may be possible, but often, healing time is required for osseointegration.

Because of the technical demands of the procedure, zygomatic implant placement typically requires advanced training and experience in implantology. Furthermore, there is a higher risk of complications such as sinus perforation, nerve damage, or improper implant angulation if the procedure is not performed correctly.

3. Indications and Patient Selection

The indications for zygomatic implants are specific and are typically reserved for patients with severe maxillary bone loss or atrophy. Conventional implants, on the other hand, are the standard treatment for most edentulous patients with sufficient bone volume.

A. Conventional Implants:

Conventional implants are ideal for patients with:

- Adequate alveolar bone (sufficient height and width).

- Stable, healthy oral tissues (gum tissue, bone, and surrounding structures).

- General health that allows for a minimally invasive surgery.

- A healthy maxilla and mandible, which are free from severe resorption, trauma, or disease.

Conventional implants can also be used in patients who need single, multiple, or full-arch restorations and are often the first treatment choice when the patient’s bone quality and quantity are sufficient for implant placement.

B. Zygomatic Implants:

Zygomatic implants are indicated for patients with:

- Severe maxillary atrophy or resorption, especially in the posterior region, where there is insufficient bone for conventional implants.

- Failure of previous bone grafts or sinus lift procedures, which have resulted in inadequate bone for traditional implant placement.

- Anatomical challenges such as maxillary sinus issues, where sinus lifts are contraindicated or unlikely to succeed.

- Congenital conditions or trauma, where the patient’s maxillary bone is severely compromised or missing.

- High aesthetic demands where the patient’s anterior maxillary arch is intact, but posterior support is needed for a fixed prosthetic.

Zygomatic implants are not appropriate for every patient with maxillary atrophy, and they should only be considered when the alveolar ridge is too resorbed to support conventional implants, and other bone-grafting options are not feasible.

4. Treatment Time and Recovery

Treatment time and recovery differ considerably between conventional and zygomatic implants due to the complexity of the procedures.

A. Conventional Implants:

For conventional implants, the treatment timeline is relatively predictable:

- Surgical placement: The procedure takes 1–2 hours, depending on the number of implants being placed.

- Healing phase: Patients typically undergo a healing period of 3–6 months for osseointegration.

- Prosthetic placement: After osseointegration, the final restoration (crown, bridge, or denture) is placed.

The overall treatment time typically spans 6–12 months, depending on individual healing rates.

B. Zygomatic Implants:

Zygomatic implant treatment may take longer due to the complexity of the procedure and the potential need for additional healing time:

- Surgical placement: More time-consuming, often taking 2–4 hours due to complexity.

- Healing phase: Generally 4–6 months before final restorations can be placed.

- Prosthetic placement: Immediate loading may be possible, but final prosthetics are usually placed after healing.

The total treatment time is typically 6–12 months, though this can vary depending on case complexity.

5. Complications and Risks

Both zygomatic and conventional implants come with risks and potential complications. However, due to the advanced nature of zygomatic implant placement, the risks are generally higher.

A. Conventional Implants:

Common complications include:

- Infection or inflammation around the implant site.

- Implant failure from poor osseointegration or mechanical issues.

- Peri-implantitis (inflammatory response around the implant).

- Nerve injury or soft tissue damage (rare).

These are less frequent and typically easier to manage in conventional cases.

B. Zygomatic Implants:

Additional risks include:

- Sinus perforation, due to close proximity to the sinus cavity.

- Nerve damage, especially to the infraorbital nerve.

- Implant misplacement, resulting in failure or functional problems.

- Infection, particularly due to the complexity of the site.

- Bone damage, from improper drilling or angulation.

Success with zygomatic implants is highly dependent on the clinician’s expertise and preoperative planning.

Conclusion

Zygomatic and conventional implants serve distinct roles in implantology, each suited to specific anatomical and clinical contexts. Conventional implants remain the gold standard for patients with adequate bone support and good oral health, offering straightforward placement and predictable outcomes. Zygomatic implants, on the other hand, are reserved for cases of severe maxillary atrophy, where traditional approaches are not feasible.

For clinicians, understanding the anatomical, surgical, and restorative differences between the two is essential for successful treatment planning. Zygomatic implants demand advanced skills, detailed imaging, and precise execution, but when properly indicated, they can restore function and esthetics in even the most compromised cases.

As full-arch implant rehabilitation continues to evolve, zygomatic implants offer a powerful solution for expanding treatment possibilities, especially in patients previously considered untreatable with conventional methods. For qualified surgeons, mastering zygomatic techniques can be a game-changer in providing comprehensive, life-changing care.